Black Lives Matter reopened an important national conversation about who we are and how our systems work. It stirred discomfort, headlines, and a lot of assumptions. At its core the discussion is not about pitting lives against one another. It is about shining a spotlight on patterns (historical, institutional, and cultural) that shape daily outcomes for people and communities.

What makes Black Lives Matter so uncomfortable for many people?

The phrase is simple and specific: Black lives matter. For some that specificity feels like exclusion. For others it feels like a challenge to long-standing systems and institutions. Both reactions are understandable, which is precisely why the conversation is necessary.

When people say they feel uncomfortable, they are often encountering three things at once:

Voice and visibility: People who have been muted suddenly have a platform.

Institutional threat: Calls for accountability can feel like attacks on systems that confer power.

Activated misconceptions: Longstanding stereotypes and myths rise to the surface and confuse the narrative.

Those reactions fuel myths like: Black Lives Matter is a terrorist group; it hates white people; it wants to retaliate against police; or it privileges Black lives at the expense of others. Those claims distract from the central point: naming a problem is not the same thing as saying other lives do not matter.

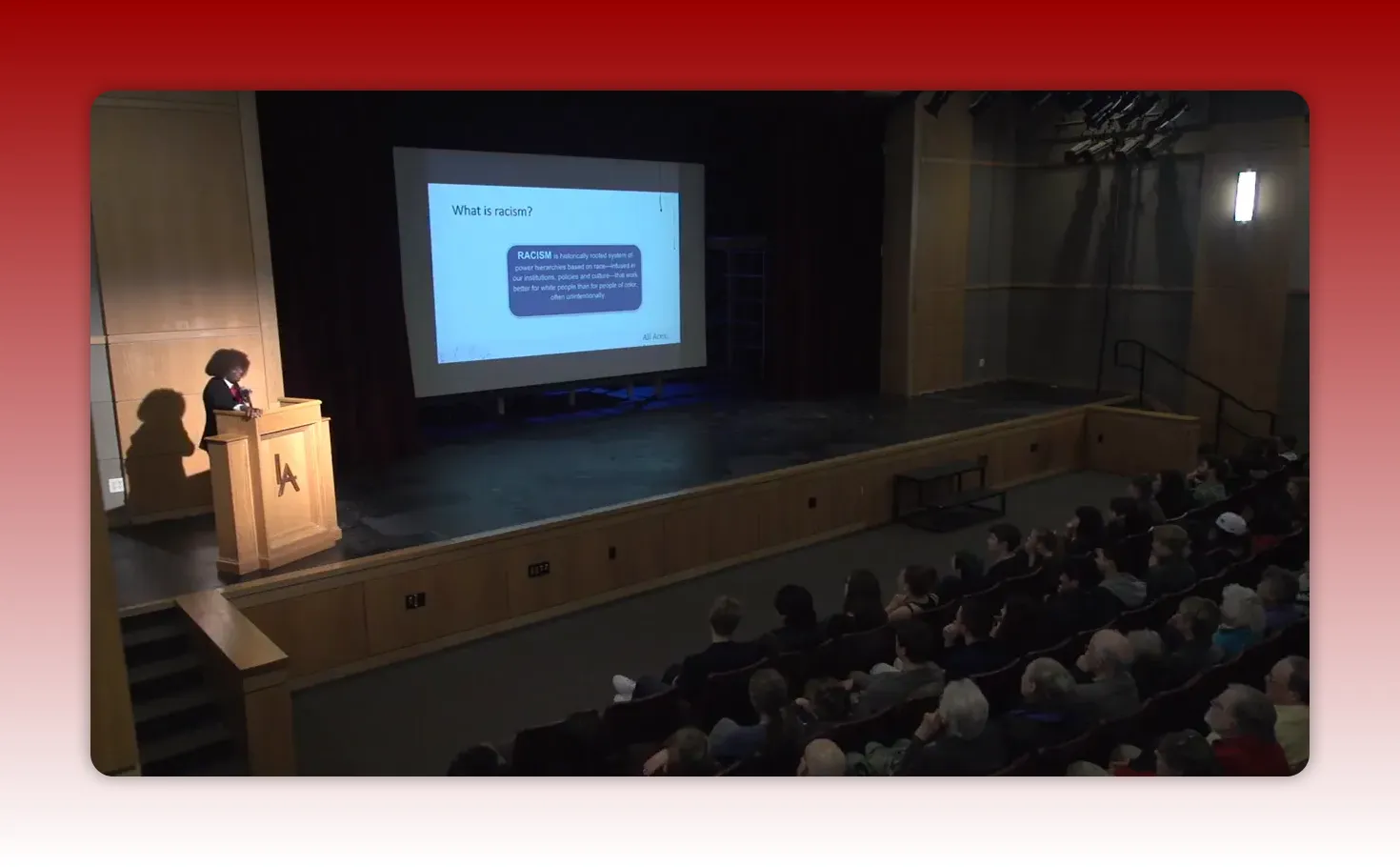

Defining racism in practical terms

Racism is often tossed around as a moral label. That reduces its meaning and keeps us from grappling with how it operates. A clearer definition: racism is a historically rooted system of power hierarchies based on race, infused into our institutions, policies, and culture. It is not only individual acts of meanness. It is structures and patterns that deliver different outcomes based on race, unintentionally and intentionally.

Think of racism as having four overlapping layers:

Ideological: The concepts and ideas we associate with specific races and ethnicities with those associated with white people reinforcing normal and the bar, and those associated with Black, Indigenous, and People of Color

Internalized: How people of any race come to accept or internalize historical ideas about them.

Interpersonal: Everyday interactions shaped by bias: microaggressions, assumptions, differential treatment.

Institutional: Policies, norms, and systems that produce unequal outcomes even if nobody intends harm.

Patterns beneath the headlines

Isolated incidents make headlines, but when you connect the dots a pattern emerges. Prejudice and bias feed decisions that get embedded into policy and practice. Those decisions compound over time and across generations. A few concrete examples illustrate how pervasive the patterns are.

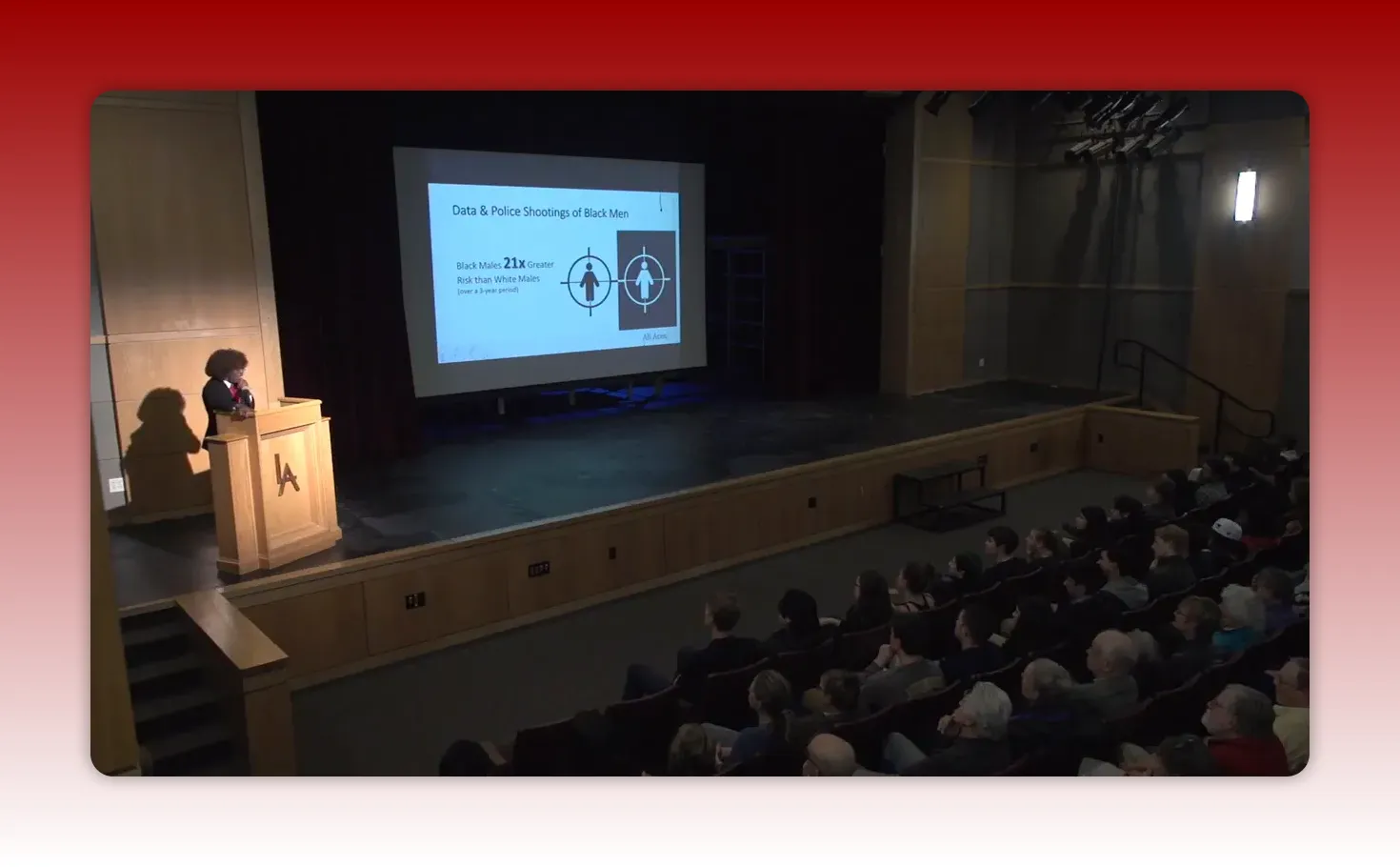

Police violence and risk

Young black men face disproportionate risk in police encounters. One measured comparison shows a young black man ages 16 to 24 has a dramatically higher likelihood of being killed by police than a white counterpart. These outcomes are not random; they are the visible end of layered bias and structural factors.

Consumer and financial discrimination

Discrimination shows up in markets most people assume are neutral. For example, major auto lenders have been found to charge higher interest rates to African American and Asian American borrowers—even when income and credit profiles matched those of white borrowers. One settlement topped $21.6 million. Most affected individuals did not realize they were paying more.

Retail profiling

Stereotypes shape who retail security stops. In one store in the Midwest, African Americans represented 10 percent of shoppers but 90 percent of shoplifting stops. Nationwide data show roughly 70 percent of shoplifters are white. That gap between reality and perception is a direct result of racialized assumptions.

Education and discipline

Students of color are suspended at significantly higher rates than white students—sometimes three times more likely. Those suspensions disrupt learning and feed into a school-to-prison pipeline, yet they often occur in schools that have less experienced teachers and fewer resources.

Housing and access

Housing search studies repeated each year show that people of color see fewer rental listings and are less likely to be shown available homes. On average, someone looking for an apartment might see 15 percent fewer options and 20 percent fewer houses. These small differences add up to huge disparities in wealth accumulation.

Hiring and names

Blind studies of resumes show a persistent effect: applicants with names that sound non-white receive roughly 50 percent fewer callbacks than identical resumes with white-sounding names. It is one of the most reproducible findings in employment discrimination research.

The science: how our brains make and act on bias

A useful way to think about bias is to separate two parts of the brain: the fast, automatic system and the slower, reflective system. The automatic system scans and categorizes in a fraction of a second. That speed keeps us alive but comes with trade-offs. It pulls in cultural messages, historical misinformation, and repeated associations.

The effect is powerful. Estimates from cognitive science suggest the unconscious brain controls between 95 and 99 percent of what we do and say. That does not make us bad. It makes us human. The problem comes when unconscious associations become institutionalized into decisions and practices.

Priming and context

Priming demonstrates how context nudges our automatic responses. A simple verbal cue or image changes what word pops into your head first. That same mechanism influences how we evaluate candidates, interpret behavior, or read a news headline. Priming works in two directions. It can deepen bias or be deliberately used to interrupt it.

Where awareness helps

There is a gap between an unconscious association and the behavior that follows. That gap is where we get agency. Consciousness creates a pause. In that pause we can invite the reflective brain to ask: What evidence do I have? What does this person need to succeed here? Does this trait actually relate to the job or the decision at hand?

Health consequences: racism as a public health issue

Racism is not only an economic or legal problem. Its physiological toll is measurable. Chronic exposure to stress linked to discrimination leads to increased depression, anxiety, hypertension, and heart disease. Research can even show effects on biomarkers and DNA that correlate with lost years of life.

Additionally, people of color often receive lower quality care. Implicit assumptions by clinicians can alter pain assessment, diagnostic choices, and treatment plans. The result is a cascade: daily discrimination increases stress, stress worsens health, and poorer health reduces opportunity.

How racism hurts everyone

When people think of racism they often imagine only the group directly harmed. But the systems that advantage one population can disadvantage many others, including white people who are poor, people with disabilities, immigrants, and other marginalized groups.

Two historical examples highlight this dynamic:

Poll taxes were designed to prevent Black citizens from voting. The policy also disenfranchised poor white citizens in large numbers. That outcome shows how a tactic framed as racial control also shrinks civic participation for the majority who paid the fee.

Social Safety Net exclusions like the initial exclusions of domestic and agricultural workers from Social Security effectively left many Black and Latino workers out of retirement protections. The result created long-run disparities in wealth and security that also reshaped political priorities and social spending.

Those decisions altered the trajectory of the middle class. Programs like the New Deal injected billions into home ownership and public infrastructure—but nearly all that capital flowed to white households. Those policies built generational wealth for some while shutting the door on others.

How to make change: practical, evidence-based steps

There is no magic fix, and the work is neither quick nor easy. But research and practice point to clear, scalable strategies that reduce bias and alter outcomes.

Diversify real social networks

Online connections are not the same as real relationships. Dinners, shared experiences, and trusted friendships change the way you see people. Networks in many communities are highly segregated: roughly 90 percent of white social networks are predominantly white. That matters because institutions hire, promote, and award opportunities based on relationships and trust. Expanding who you know widens the circle of who benefits.

Slow down and create procedural pauses

Fast decisions favor the unconscious brain. Build pause points into processes where bias matters: interviews, hiring panels, lending decisions, disciplinary meetings. Structured interviews, standardized scoring rubrics, and blind review of applications reduce the influence of like-me bias and first impressions.

Use counter-stereotypical images and stories

Stereotypes persist because we repeatedly see the same narrow images. Show the broader range: scientists, engineers, artists, entrepreneurs, caregivers. When people regularly encounter varied portrayals, automatic associations weaken.

Learn and teach full history

Understanding the policies that shaped wealth and opportunity matters. The New Deal, redlining, restrictive covenants, and exclusionary practices in the social safety net are not ancient artifacts; they are the building blocks of today's inequalities. Teaching the full story reframes debates from moral blame to structural diagnosis.

Audit and measure

Regular audits of outcomes reveal where inequities hide. Does your organization show disproportionate suspensions, higher loan denials, or skewed hiring outcomes? Data make it possible to target interventions and measure progress.

Design for accountability

Create policies that institutionalize pause points and checks. Examples include diverse hiring panels, anonymized resume reviews, equity impact assessments for new policies, and mandatory trainings that are interactive and sustained rather than perfunctory.

Practice humility and curiosity

Most people who perpetuate bias are not malicious. They are acting on an inherited set of assumptions. Holding space for vulnerability—admitting what you do not know, asking questions, listening deeply—builds trust and opens pathways for change.

An actionable checklist to get started

Map the decision points in your organization where race might affect outcomes: hiring, lending, discipline, contracting.

Add structured pauses to those decision points. Require rubrics and written rationale.

Audit results annually and publish findings with corrective action timelines.

Expand networks by sponsoring cross-community events, shared projects, and mentorship that crosses racial lines.

Use blind or anonymized assessments where feasible to reduce name- or image-based bias.

Include counter-stereotypical narratives in communications, recruitment materials, and curricula.

Train for structured empathy—techniques that help people pause, reflect, and ask job-related questions instead of narrative-based assumptions.

Core framing quotes

If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.

That proverb (BTW not confirmed to be an African proverb) captures the scale of the work. Productive change requires collective, durable effort rather than isolated heroic acts.

An error does not become a mistake until you refuse to correct it.

Mistakes are inevitable in complex systems. The crucial step is to acknowledge them and commit to correction.

Frequently asked questions

How do I distinguish between individual prejudice and systemic racism, and why is this distinction crucial for understanding racial justice efforts?

Dr. Atyia Martin's work, drawing on her expertise in resilience and social equity, likely emphasizes a critical distinction between individual prejudice and systemic racism. This differentiation is not merely academic; it is fundamental to understanding the scope of racial injustice and formulating effective solutions.

- Individual Prejudice (Racism as a personal belief): This refers to preconceived negative opinions, attitudes, or feelings toward people based on their race. It often manifests as stereotypes, discrimination by individuals, or conscious/unconscious biases. While harmful and impactful, it is localized to individual actions and thoughts.

- Systemic Racism (Racism as a system of power): This refers to the embedded and entrenched discriminatory practices and policies within institutions (e.g., legal, educational, housing, employment, healthcare) that, intentionally or unintentionally, create and perpetuate racial inequality. It operates through historical practices, cultural norms, and legal structures that advantage one racial group (typically white people) while disadvantaging others.

This distinction is crucial because:- It informs solutions: Addressing individual prejudice requires education and personal reflection, while dismantling systemic racism demands institutional reform, policy changes, and a critical examination of power structures.

- It clarifies responsibility: While individuals are responsible for their biases, systemic racism implicates entire societies and their institutions in perpetuating injustice, requiring collective action.

- It explains persistent disparities: Many racial disparities (e.g., wealth gaps, incarceration rates, health outcomes) cannot be fully explained by individual prejudice alone; they are the cumulative result of systemic barriers.

What practical steps can individuals take to combat racism and support racial justice?

Drawing from her background in community resilience and equitable development, Dr. Atyia Martin would likely advocate for a multi-faceted approach where individuals can take concrete steps to combat racism and support racial justice. These steps move beyond passive non-discrimination to active anti-racism:

- Educate Yourself Continuously: Commit to ongoing learning about the history of racism, its manifestations, and the experiences of marginalized communities. This includes reading books, articles, listening to podcasts, and engaging with diverse perspectives.

- Self-Reflect on Biases: Honestly examine your own implicit biases and prejudices. Understand how your own upbringing, media consumption, and social circles might have shaped your views. This critical self-awareness is foundational.

- Speak Up and Intervene: Challenge racist jokes, comments, or microaggressions in your personal and professional life. Learn effective ways to interrupt biased conversations and educate others without shaming.

- Support Just Policies and Organizations: Advocate for local, state, and national policies that promote equity and justice (e.g., fair housing, criminal justice reform, equitable education funding). Support organizations that are actively working on racial justice issues through volunteering or donations. Within organizations that you are already connected to, advocate for policies that address know racial inequities.

- Engage in Difficult Conversations: Be prepared to have uncomfortable but necessary conversations about racism with family, friends, and colleagues. Approach these dialogues with empathy, a willingness to listen, and a commitment to shared understanding.

- Demand Accountability: Hold institutions (workplaces, schools, government) accountable for their diversity, equity, and inclusion commitments. Participate in efforts to create more equitable environments.

What common barriers or resistance should I expect when discussing racial justice? What strategies should I use to navigate these challenges?

There are several common barriers and forms of resistance that impede progress when discussing racism and racial justice. These include:

- Discomfort and Avoidance: Many individuals experience discomfort when discussing race, leading to avoidance, silence, or changing the subject.

- Denial and Dismissal: People may deny the existence or severity of racism, particularly systemic racism, often citing individual success stories or claiming reverse discrimination.

- Fear of Guilt or Blame: White individuals, in particular, may feel personally blamed or shamed, leading to defensiveness rather than engagement.

- Lack of Understanding of Systemic Issues: A common barrier is the inability to grasp how racism operates beyond individual acts of meanness, failing to see its structural implications.

- Tokenism and Performative Allyship: Superficial gestures of support without genuine commitment to structural change.

- Fatigue and Apathy: A sense of exhaustion from ongoing discussions about race, or a belief that progress is impossible.

Strategies for Navigating Challenges and Fostering Progress:

Here are some strategies focused on building capacity for dialogue, understanding, and action:- Cultivate Psychological Safety: Create environments where people feel safe enough to ask questions, make mistakes, and engage authentically without fear of immediate condemnation.

- Focus on Systems, Not Just Individuals: Frame discussions around policies, institutions, and historical context rather than solely blaming individuals, which can reduce defensiveness and encourage collective problem-solving.

- Emphasize Shared Humanity and Mutual Benefit: Highlight how dismantling racism benefits everyone by creating more resilient, equitable, and just societies.

- Provide Concrete Examples and Data: Illustrate systemic issues with clear, factual examples and data to help bridge abstract concepts to lived realities.

- Encourage Active Listening and Empathy: Promote skills for deep listening and understanding different perspectives, even when they are challenging.

- Start Locally and Incrementally: Emphasize that significant change often begins with small, consistent actions within one's own sphere of influence (family, workplace, community).

- Build Coalitions and Cross-Racial Alliances: Foster collaboration among diverse groups to strengthen efforts and share the burden of advocacy and change.

- Foster Resilience and Sustained Commitment: Acknowledge that progress is not linear and requires sustained effort, encouraging individuals and groups to build resilience against setbacks.

Why does saying Black Lives Matter feel exclusive?

The phrasing highlights a specific history of marginalization. It does not imply other lives do not matter. Specificity is a common rhetorical tool: naming a problem clarifies where resources and attention are needed to patch systemic inequities.

Isn’t racism just about overt hatred?

Racism includes overt acts of hostility but is also about embedded systems—laws, policies, institutional practices—that consistently produce unequal outcomes based on race, often without explicit malicious intent.

Do unconscious biases mean people are irredeemably racist?

No. Unconscious biases are part of the human cognitive toolkit. They can be reduced and redirected with deliberate practices: diversified relationships, structural pauses in decision-making, counter-stereotypical exposure, and continuous self-reflection.

If racism is institutional, what can individuals do?

Individuals play multiple roles: neighbor, colleague, manager, voter. Each role includes specific levers; who you mentor, who you hire, what you vote for, which programs you fund. Small, consistent actions across many individuals shift institutional norms.

How do we avoid making white people feel guilty while addressing structural racism?

Reframe the work away from guilt and toward shared problem solving. Emphasize how structural inequities harm many groups, including poor white people. Invite practical actions that strengthen institutions and communities for everyone.

What are the first three practical steps an organization should take?

1) Audit current outcomes to identify disparities.

2) Add structured pauses and rubrics to key decisions.

3) Expand networks and recruitment pipelines to include diverse, counter-stereotypical talent.

Final note

Real change is messy, persistent work. It asks us to be honest about history, to redesign processes that reward comfort over fairness, and to listen to voices that have been marginalized for generations. The work calls for both public policy fixes and private, day-to-day practices: slowing down, noticing, and choosing differently.

The cavalry is not coming. Progress will come from collective, sustained effort: building relationships across difference, redesigning institutional decision points, and committing to the long haul.

This article was created based on the video Lawrence Academy Presents Dr. Atyia Martin.